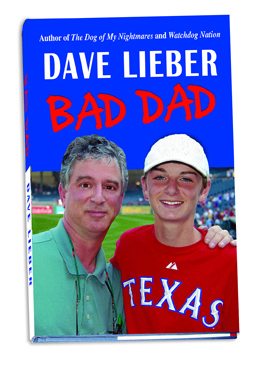

BAD DAD

By Dave Lieber

A newspaper columnist investigates the shenanigans of a small-town police department — then pays a price for it. After he orders his misbehaving 11-year-old son to walk home from a local restaurant, police arrest the dad for two felony counts. A true-story thriller about parental responsibility, small-town corruption and the consequences of being a public figure.

(This true-story mystery thriller is also a parenting book about parental responsibility, child-rearing practices, child discipline and bad parenting.)

978-0-9708530-9-7

$23 hardcover

Watch the video book trailer here.

The following is a true story.

Chapter One

I first got stopped by an officer from the small-town police department about a month after moving to Texas. My new neighbors in Fort Worth had warned me about a strip of roadway across the street in the neighboring city of Watauga. That strip contained Watauga’s police headquarters, City Hall, the biggest Baptist church in town and a drive-through McDonald’s. A speed trap, they said. I remembered that fact a little too late after I forgot to brake coming down a hill and saw flashing police lights in my rearview mirror. When asked, I told the officer I was new in town, learning my way. He let me go with a warning.

The second time I got summoned by the city came a few weeks later when the town’s “honorary police chief” demanded that I come see him in his office. He was the Watauga city manager and former police chief, and the honorary title allowed him to keep his gun. I knew why he wanted me.

In my new job as a metro columnist for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, I had written my first column about Watauga City Hall. Maybe he liked it. I drove less than a mile from my new house to his City Hall office situated on that strip. Inside, dark-eyed Bill Keating ordered me to sit, then slammed a copy of my newspaper on his desk.

“Don’t you dare write another word about Watauga, Texas, without talking with me first! You got that, son?”

“Yes, I do.”

“I’m serious, son.”

“Yes, sir.”

The third time I got stopped, a police officer pulled me over and asked to see my driver’s license. When he saw my name, he surprised me by introducing himself and shaking my hand. He thanked me for supporting him in a battle with his superiors. Lucky me. I had written a column arguing that after a gallant act he had performed sheltering a young abused girl, he was treated unfairly and punished. After the public learned of his story, they rallied behind him. Before this traffic stop, he and I had never met. We talked by the side of the road. Again—no ticket.

The fourth time came several years later, after writing many more columns about the town’s police and fire departments and city government. By then, I was known among the officers for my writings. Some liked me; others didn’t. Once again, though, I got lucky. The officer who stopped me for speeding let me go with a warning. Later, though, he was scolded by the chief, who heard about it on the police radio. The officer told me later that his chief chewed him out because he wanted to make sure the officer understood the department’s informal rule:

“You never let Dave Lieber go with only a warning.”

Then there was that fifth time. The stop that has made all the difference.

Here’s what I remember:

Aug. 13, 2008

My son Austin, 11, and I are eating breakfast inside that McDonald’s on the strip. He’s my boy, my pride, so much like me. Attentive. Creative. A fast car in the fast lane. I try to get Austin to slow down, but he moves faster than anyone I know. On the basketball court or running down the stairs at home. He can’t stand waiting. He has to keep moving.

On this day, though, things don’t go well for either of us. Austin finishes his pancakes. He wants to go. I’m not done. I start sipping a hot coffee and read the newspaper. This drives him batty. He wants to go home and call a friend so they can play.

“Sit and wait until I’m done, please! I want to finish my coffee.”

“Let’s go, Dad! I want to go now!”

“I’m telling you: sit and wait until I’m done.”

“No, let’s go.” He says it louder. “I want to leave now!”

“Shut up! We’re in a restaurant. Go sit and wait for me at that table. If you don’t, I’m going to let you walk home. You can think about the way you behaved during your walk.”

Several men are sitting at nearby tables by themselves. All have their backs to us. But we are loud enough that they can hear.

Next thing I know, I’m fast-walking out the door. Austin is right behind me. I speed up. He speeds up. Outside in the parking lot, I unlock the car, jump in and then lock the doors before he can get in.

I turn on the engine and back the car out. He’s still pulling on the handle. When he sees the car moving backward, he lets go but chases me for several steps. Then he stops.

He’s standing in the parking lot, crying and bewildered.

I drive away.

Later I learned that several adults gathered around him. One asked Austin if they should call the police. Austin, then 5-foot-3 and capable of walking the 7/10th of a mile, or six blocks, through our neighborhood back to our house, shrugged his shoulders. He wasn’t sure what to do.

I drive up the road to cool down. I call my wife, Karen, at work and tell her what happened. She tells me to turn around and get him. I make a U-turn.

Ten minutes or more have passed. If he’s not at McDonald’s, I’ll cruise the route he would take and make sure he’s headed home. But in front of McDonald’s, as I pull in, I see a small crowd. Several men turn and glare at me.

I see two Watauga police cars. The officers are waiting for me.

So that’s the fifth time I got stopped by Watauga authorities. The one that in the days ahead would make it possible for me to lose so much: my son, my career of 30 years, my job, my good name.

Take your worst 10 minutes of any day. You acted terribly, but maybe nobody knew. Or at least you thought so. Then imagine that everyone finds out. Everyone.

Within days, your foolishness flashes around the world. What you did is featured on the TV news, in newspapers, on radio talk shows and overheated cable-television debates, and in blogs. Everybody has an opinion about you and what you did in those 10 minutes.

Everybody decides whether you are a good dad or a bad dad.

One of the officers greets me by name.

“You’re Dave Lieber, right?”

He asks to see my driver’s license. He tells me that terrible things could have happened to my son while I was gone. He tells me to stand by myself and wait by the front of McDonald’s.

I stand there, like a rock. Eventually, an officer introduces himself by name, but he says it so fast I can’t make it out.

“Here’s what’s going to happen. We’re going to do a report for today’s occurrence, OK? We’ve gathered witness statements from all the witnesses here. We are not going to take any action today with you, which we could. We are going to refer this case to Child Protective Services. We are going to turn it over to our investigation division, and they will give a referral to the district attorney’s office. I don’t know what the outcome of that will be. That’s beyond my area.

“But I just wanted you to be aware of the severity of the circumstances today—I’m sure you probably already are aware of that—and the actions that could take place. We are not going to do that, though, today. And we will leave it up to the process down the road to see what happens. But just keep in mind and be aware that there could be a later date that you will have to answer to a higher cause than us, OK?”

“Yes, sir.”

“So keep that in mind. Is there going to be a problem between you and your son now?”

“No.”

Another officer approaches.

“Obviously, having had to stand here and think of it, you understand everything that could go wrong, and what our responsibilities are as parents?”

“I do. Thank you.”

He says we can go home.

We are in the car, driving home.

“Sorry, Daddy.”

Those are the first words out of Austin’s mouth. I am relieved to hear them.

“Well, there could be some serious stuff coming out of this,” I say. “This will go everywhere.”

He tells me that after I left him and the men gathered around, he said he told them: “It was my fault. I was just being mean.”

One of the men responded, “No, it doesn’t matter what you did. Your dad should never drive off like that.”

He also tells me that when the officers found out who his father is, they called in “a higher officer.”

Driving us home, I look down and see I’m still holding the cup of coffee I bought at the restaurant. The coffee is cold now.

That’s what I remember.

[end of Chapter One]