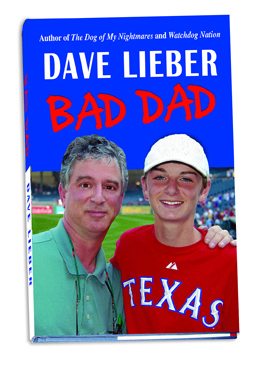

By Dave Lieber

The Watchdog Columnist/The Dallas Morning News

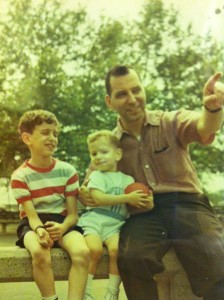

I’ve been away. My father died last week. He was 90, having passed that momentous occasion a few days earlier. He almost crossed the finish line. Our family was supposed to spend Friday in a cabin on a mountaintop in North Carolina, where he was born. Instead, we buried him that day. My younger brother Bennett and I were honored to deliver eulogies at his funeral in Manhattan, two blocks from the apartment where we grew up, a place my dad lived in for 54 years. I hope you don’t mind if I share what I said:

On behalf of the family, thank you for coming today. Thank you, Rabbi Miller, for your wonderful words.

I am David, the oldest son of Stanley. And I want to tell you there were actually two Stanley Liebers, born in 1922, of New York, New York. The first one was an outward Stanley Lieber. He created some of the greatest characters we know, including The Hulk and Spiderman. He changed his name to Stan Lee.

The other Stanley Lieber – this one (pointing at coffin) – was an inward man for the first seven decades of his life. He was the husband of Denise and father to David and Bennett. But 16 years ago, when my mother was dying, we had a deathbed conversation. It’s not something I shared with too many people before. But she called me over and she said, “Your father cannot make it without me.”

“What do you mean?”

“Just trust me. Your dad cannot make it without me. I’m worried about him.”

“What do you mean?!”

She wouldn’t tell me. On its face, it seemed accurate. Denise took care of Stanley in every way. She did everything for him. He was totally dependent on her. He came from a small town in North Carolina. She was a big city girl from Manhattan. She forced him to come to New York City in 1958, but he wasn’t prepared for what would happen after she passed away. FDR never bothered to tell Truman about the Big Bomb. Denise was FDR and Stan was Truman.

They met in 1955 at a singles event at a country club on a two-lane road in Pike, New Hampshire called the Lake Tarleton Country Club. It was a place where Jewish singles could go. I know this club because years later my summer camp was a half-mile down the road, and I used to run to it for a mile run back and forth. It was abandoned by then, but I knew that’s where it all began.

Stan wanted to be an actor. Then he wanted to be a journalist. He actually studied at one of the finest journalism schools in America, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He got his degree, but typical of my dad, he said there was no money in journalism. He became a Certified Public Accountant.

My goal in life is to prove him wrong. His greatest gift to me was to send me out every night to fetch the newspaper at 6 o’clock. The New York Post final edition. That simple act of giving me a dime and sending me out to get his paper so he could see how much money he lost in the stock market that day was enough to get me excited about the newspaper world. We would read the paper. We would discuss the paper. And ever since I moved away, he sent me clippings — underlined, taped, stapled — of stories I had just read the day before.

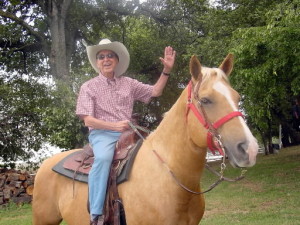

When my mom died in January, 1996, slowly, slowly, he launched his second act. In America, I don’t think there’s a higher calling than to be called a volunteer – with apologies to you, Rabbi, for that. But as you know, he became a volunteer for the Big Apple Circus and many Jewish causes. But what he really did was to volunteer to help his city. New York became his second girl. He talked up the city to everybody. He talked about real estate happenings and the people and the culture and the museums. Just about everything he could. And he got so good at it and talked to so many people that he became an unofficial ambassador for New York. In my mind, he became part of the New York City skyline.

I picked up on this and began to write about it some in my Texas newspaper column. And on Sept. 11, 2001, I called him, and he asked me, “How are you doing?” And, without thinking, I replied, “Good.” He answered, “You’re doing good! You’re doing good? My city is in tears. We have a tragedy here. And you’re doing good!”

That’s how I began my story in the newspaper about him. That story left an indelible impression because people in Texas began to see New York through the eyes of this one man. To this day, when I travel about Texas, I’m often asked, “How’s your father? How’s his city?” They were linked in the Texan’s mind as brother and sister. But actually, it was more like boyfriend and girlfriend.

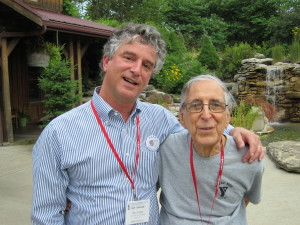

There are a few things I want you to know about him. You all remember the movie Wedding Crashers. My dad was a conference crasher. He figured out early on that if he paid $150, he could come with me every year to the National Society of Newspaper Columnists convention, where he could meet all these famous columnists and talk to them and go on tours of cities that we would otherwise probably never get to visit. I’ll never forget when we went to the conference in Indiana a couple of years ago. The columnists visited French Lick Resort, one of the greatest hotels in America. Within an hour after our arrival, everybody in that hotel, from the concierge, the bellmen, the bartenders — they all knew me as “Stan’s boy.”

And I remember watching across the giant lobby of this hotel, and there was a group of columnists from all over the country on a tour. And there was this little man with his white baseball cap and his blue polo shirt, his white shorts that went down to his knees and his white sox pulled up high, and his little white sneakers. And he was running around with his cane, walking with all the columnists. He became friends with these columnists. He traded letters with Jeffrey Zaslow, who wrote The Last Lecture and died tragically in a car accident earlier this year. He knew more about my columnist friends than I did. He would call me and say so-and-so has a book, and so-and-so just got syndicated.

My one regret is that at our last conference together, he asked me if, at the final dinner, he could stand up and talk to them. I reverted from a 53-year-old man to a 10-year-old boy. And I said, “Dad! Please don’t! You’ll embarrass me. Don’t talk.” My wife Karen said, “Let him talk. Let him talk.”

“No, no, no. He’ll embarrass me.”

And I realized after that, I should have let him talk because he wouldn’t have let me down. He would have said the most wonderful things.

And now I’m getting letters from columnists around the country – from Massachusetts, Florida, Virginia, Indiana, California – telling me how much they enjoyed my dad. He really was one of us columnists. He had opinions. He kept up with the news. He just didn’t bother to write about it.

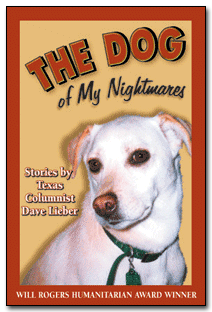

Also, something else you don’t know about him: that education he received at UNC for journalism paid off. He became one of my two copy editors for all my books. I hired a professional copy editor, and then I’d ship it to Stan. Many times, he found errors that the other editor and I both missed. He knew language. He had full command of grammar, spelling, punctuation and logic. He helped me immensely.

And of course, he gave out my books to everyone he met. He would send me a letter: “Send a book to Dr. so-and-so. Send another to Nurse so-and-so.” I counted: there were a 110 of these books that went out. Many members of the New York medical community have my books.

I want to thank the people from his apartment building. I want to thank all the friends who are here today. I want to thank my brother Bennett and Nancy and their children, Avery and Nicole, because while I have been away for 30 years, you all took care of my dad. And you did it so well. I really appreciate everything you did for him.

I want to thank my wife, Karen, and Desiree, Jonathan and Austin, especially Karen because what did he love next to life itself? Your fudge.

I want to thank my Uncle Howard and Aunt Renee. Renee called every day to check on him. I want to thank my Aunt Sandy who came up from Florida.

Finally, as a writer, my job is always to take the small story, the seemingly insignificant story, and give it a universal truth. In Stanley’s case – the biggest challenge in our society now as we face the next few decades is what do we do with the elderly? How do we help them live comfortably, live well and live strong? Rather than slide into isolation and depression and loneliness after my mother died 16 years ago, Stan Lieber started a whole new life. His second act. And for all of us here he became a role model to show us, when we get older, how we can live our lives and touch people. This is what we’re supposed to do.

Stan grew older, but yet he seemed to grow younger. He discovered the secret of life — what humanity is all about. Connecting with others. It’s about friendship. It’s about happiness. The proof is this business card. He sent me this last week. He told me he needed another 500. It has his name, Stanley Lieber, CPA. His address, his phone number, his email address. How many 90-year-old men want 500 business cards? He wanted to connect.

As the other Stan Lieber, born in 1922 of New York, New York, figured, there was room for only one Stanley Jesse Lieber in New York, the city where all my dad’s dreams came true.

The author, Dave Lieber, is a columnist and public speaker based in Texas.

This was posted July 30, 2012